Ancient Egyptians: Feminist thought leaders?

The fact that women occupy positions of power within society does not serve as a subversion of the patriarchy’s hegemony. Consider Margret Thatcher’s rise to power in the 1980s for instance. At the time, her election was often conflated with a significant triumph over the patriarchal power structures that were pervasive within the United Kingdom. To claim that Thatcherite libertarianism enjoyed any tangible victories over the patriarchy is largely untenable. Yet many have argued that her tenure served to reinforce the existing inequalities between men and women. Similarly, Egyptologists have mistaken the prevalence of female kings for a progressive bend in the arc of justice. Hatshepsut’s reign during the 18th dynasty is often leveraged as the crux of this narrative. The contextual idiosyncrasies of her rise to power seemingly offer evidence for this argumentation. In her monograph Cooney outlines three capacities in which Hatshepsut was unique. First, she was “the only woman to have ever taken power as king in ancient Egypt during a time of prosperity and expansion.” Second, unlike the many mothers who held power on behalf of their sons, Hatshepsut “acted as regent for a boy who was not her son.” Lastly, she held the “longest tenure of any female leader of ancient Egypt.” Yet in spite of these distinctions, she was no exception to the pernicious outcomes invariably engendered by many of the Egyptian queens. Just as the others did, Hatshepsut served as a buttress to the authoritarian patriarchy which maintained its grip over the 18th Dynasty. The crucial note here is that this conclusion does not seek to level criticism at Hatshepsut but rather to highlight the entrenchment of patriarchal power structures in Ancient Egypt. A patriarchy, that irrespective of the Dynasty's leader, was able to ensure that the trajectory of their society was only influenced by men.

In her introduction, Cooney outlines the circumstances under which female rule was permissible. Unsurprisingly, a woman’s ascent to power was confined to the instances in which it was commensurate with the patriarchy’s incentive structure. Cooney claims that each Egyptian Queen was “put in power by an Egyptian system that needed her rule.” Hatshepsut was no exception, her rise to power was engendered by this exact Machiavellian pragmatism or as Cooney labels it “realpolitik”. In Hatshepsut’s case a succession crisis created a need for leadership. By virtue of this necessity her very rise to power sought to prop up the existing power structures and by extension the patriarchy. This becomes increasingly evident when you consider the criteria which dictated that Hatshepsut specifically should assume power. First, it was crucial to ensure that power remained within the royal family. Moreover, her position as Egypt's highest priestess was likely seen as an added benefit as it gave her ascent a theological justification that rendered her position difficult to challenge. Yet perhaps most perniciously, the mechanism which allowed for Hatshepsut’s reign, chose her on the grounds that she would not pose a threat to the existing power structures. Here, Cooney references testimony from Ineni, a courtier who likely facilitated Hatshepsut’s rise to power. Cooney cites Ineni’s tomb text in which he claims “all the elites were thrilled to have her [Hatshepsut] in charge, that she wasn’t throwing her weight around or being difficult in any way.” Ultimately, her ascent to power was orchestrated on the expectation and condition she would become a figurehead for the already powerful. An expectation Hatshepsut would meet.

The tangible ramifications of Hatshepsut’s rule overwhelmingly reinforced the establishment. Broadly, we can characterize her policy with a strict adherence to the aforementioned expectation, an expectation to serve the patriarchy. As Cooney frames it in her introduction this was an outcome Hatshepsut would have held very little influence over; as all female leaders in Egypt were preordained to become “mere pawns of a patriarchal system over which they had no control and could never hope to alter in the long term.” Hatshepsut in particular was forced to pander to the elites in order to maintain her position. A fact that was yet another consideration in her ascent to power. Hatshepsut's kingship was a façade behind which the landed gentry could hide while simultaneously benefiting. Cooney references the “explosion in nonroyal monument creation” as evidence that, under Hatshepsut there had been a shift in the “balance between king and elite.” Hatshepsut’s reign allowed the Egyptian landed gentry to garner unprecedented power. This power was not limited to the financial capital required for such an explosion in monument construction but it also included a significant increase in political capital. Cooney notes that throughout her reign Hatshepsut “ created a tremendous number of new jobs for elites.” Just as capital begets capital, this new found influence would only grow and allow the elites to further entrench themselves and continue to perpetuate the patriarchy.

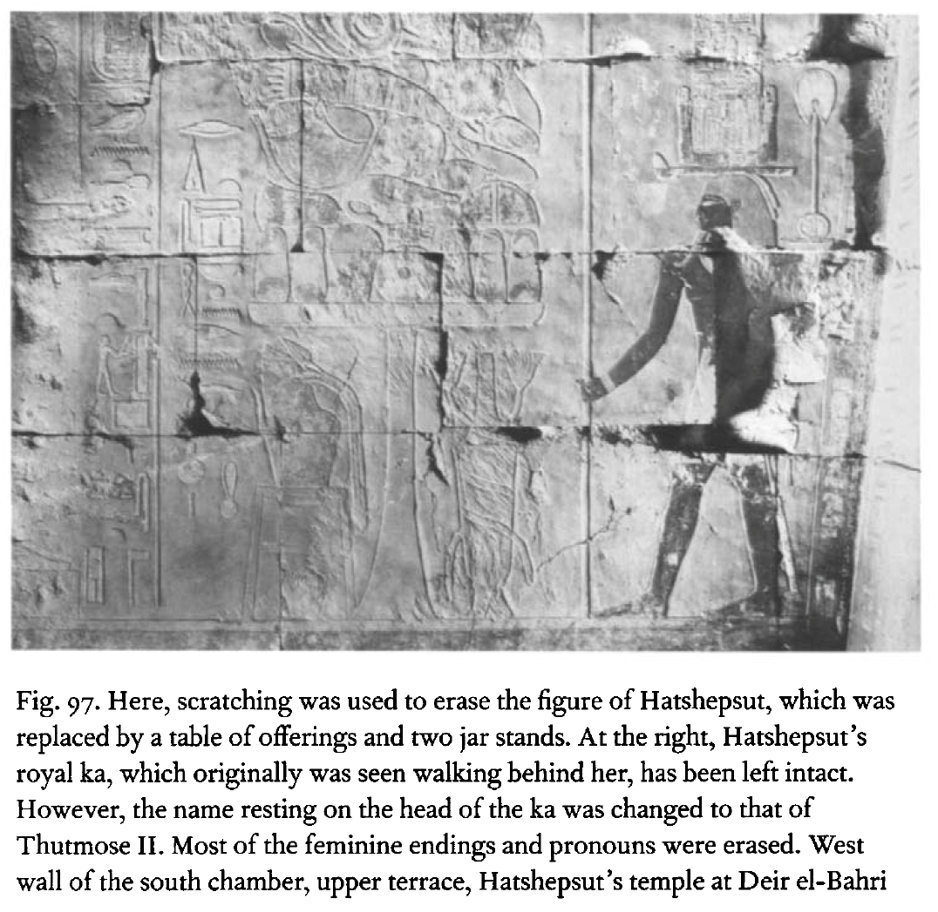

A robust and differentiated analysis of Hatshepsut’s reign must also examine the implicit subversion of patriarchal narratives. That is to say that, symbolically having a seemingly successful woman in a position of power does carry water. Hatshepsut’s mere existence might have been impactful for future generations of women seeking direction. This is a form of empowerment that could have spurred a bend in that fabled arc of justice. Yet Hatshepsut was unable to achieve this level of influence. The first reason for this is the systematic erasure that buried her very existence for centuries. The ramifications of which are virtually irrevocable. In his Proscription of Hatshepsut Peter Dorman remarks that “the systematic erasure of Hatshepsut’s name and figure from the kingly monument some years after her death has, inevitably, become a lens through which historians have viewed the events of her life and reign.” The erasure, largely carried out by Thutmose III, has systematically warped the narrative around Hatshepsut’s reign. Yet the outcome of this campaign was far more sinister than merely engendering harmless misconceptions; the erasure served to reassign credit away from Hatshepsut to other male kings. Figure 1.1 (see appendix) illustrates how the reassignment was carried out. In this instance, not only was a depiction of Hatshepsut removed but her inscription was replaced with that of Thutmose II. This campaign was only exacerbated by the fact that Hatshepsut was often depicted with masculine features making it simple to change the inscriptions and reassign credit.

Hatshepsut’s reign ultimately propped up the patriarchy in three key respects. First, the necessity of her rule meant she performed an invaluable function on behalf of the establishment. That is to say her rule allowed for those in power to maintain their grip. Second, throughout the trajectory of her reign she was forced to acquiesce a great deal of financial and political capital to those who sought to perpetuate the patriarchy: the existing elites. Finally, the erasure campaign which followed her reign served to mitigate any positive future benefits that might have lended greater credence to egalitarian movements while simultaneously reassigning credit for her achievements to the men that preceded her rule. Despite the fact she lacked both the agency and power to stop this outcome, Hatshepsut’s rule ultimately served to further entrenched the patriarchy.

Figure 1.1